We are pleased to share news of a new book relevant to…

Why the future's bright for women's co-ops in Turkey

Betsy Dribben, Director of Policy for the International Co-operative Alliance, discovers why the future for women's co-operatives in Turkey has never been brighter.

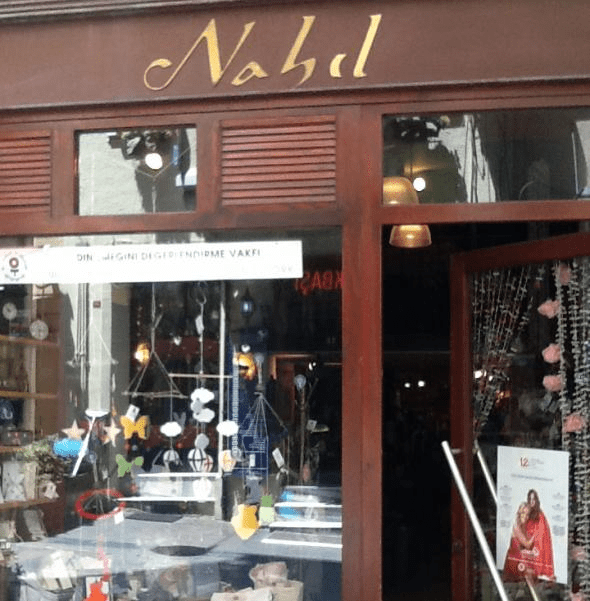

On an Istanbul backstreet, a shop window features a display of hand embroidered towels, beautiful scarves and handmade children’s toys. The shop, Nahil, is more than just a sweet spot in a busy city. It is testament to the Turkish women’s co-operative movement and its founder, Sengul Akcar.

Her route to co-operation was circuitous. In University she studied construction engineering. Her first job was organising co-operative housing in Izmir, Turkey. The goal was to create 30,000 homes, which each person would design to suit their needs. The idea was pioneering, and ultimately the time was not right for it. The project failed and Ms Akcar had to move on.

She pursued a masters degree in public policy. Writing a paper on early childhood care services for the poor, she was so troubled by the lack of services she created the Foundation for the Support of Women’s Work (FSWW).

It was the late 1980s, and the feminist movement was beginning in Turkey. “We used the strengths of the poor to grow FSWW,” She recalls. “Poor women do know things. They know how to cope with poverty, how to work together. They have strengths.”

She put those strengths to work, establishing pilot child care programmes and developing those that worked. In an early childhood education programme, mothers provided the services, not outside professionals. They organised their centre, did the fundraising and ultimately provided training.

“We came to the conclusion that as these succeeded, they should be autonomous, not under the FSWW," she says. "We drew up a set of principles that these mothers wanted. Participation was important, empowering them was important. A democratic approach and transparency were all part of the list. We concluded that it should be a co-operative model.”

They established the first co-op in 2001. Four years later there were almost 30. They set up a network; a support centre with training programmes on how to organise, establish and run co-operatives, including leadership training, so members could address family and community issues.

Today there are over 120 women’s co-ops and the future is bright. The co-ops pay for their own teachers. “It is their own business,” says Ms Akcar.

To enhance what the co-ops were doing themselves, Ms Akcar set about lobbying the Turkish government to do their part. She began by seeking examples of social co-operatives to see how they worked. They connected with women’s co-ops in Italy, Nicaragua and Sweden, and they still keep in touch.

Thanks to two female political leaders in the Ministry for Family and Social Policies, Faetma Sahin and Askin Asan, this summer the Turkish Parliament is expected to pass a law which eliminates legal bottlenecks and helps women's co-ops grow.

Ms Akcar says: “Women’s co-operatives in Turkey are very optimistic. Women in poor areas want to organise co-operatives. They're ready to find their way but we need this law.” When the law is in place, she estimates upwards of a million people will join women’s co-ops.

Nahil, an Ottoman word for “prosperity, unity and solidarity”, is thriving too. Run by Sule Alpaslan, it provides over 600 women with an outlet for their crafts and showcases ten products from co-operatives, including soap, dried fruit and olive oil. Co-ops affiliated with the shop are trained in how to write business plans, among other skills.

The Foundation is also forging ahead. Over 1,000 children now benefit from 22 day care centres nationwide, and children from low income homes in the Istanbul area have access to play groups, toy libraries and more.

The World Bank has recognised the Foundation's success and in 2007 Vanderbilt University accredited its approach to teacher training and day care. Women’s co-operatives in Turkey are thriving, thanks to Sengul Akcar's vision and the many women in the movement with a can-do attitude.